One of the most frequent conundrums faced when debating the existence of hidden animals is rationalising the apparent lack of significant numbers to sustain a population. Even more difficult is to accept an introductory population that appears to have been seeded by complete accident. Is it possible such a population of predatory cats could have established itself in Britain?

As discussed in my previous articles I don’t believe the issue lies with Britain’s human population, available wilderness or spatial arrangement. In order to investigate the possibility a big cat population we

need to consider and compare an array of scenarios and examples of other species introduction, re-establishment or naturalisation elsewhere in the world.

Humans have a great ability to misinterpret the context in which living organisms interact with our modern landscape. In the majority of British gardens less than 15% of plants are native to our own shores, even our lawns are foreign most of which contain domesticated grass strains from the Americas. Naturalisation as the word indicates can be a natural process of succession where all species within an ecosystem jostle for position some will become extinct, some will thrive, and others will change to fill new niches.

In Britain our separation from mainland Europe has strengthened the boundary’s to what is native and what isn’t, except from the last ice age anyway. A list of species naturalised to Britain can be seen in schedule 9 of the Wildlife & Countryside Act 1981 giving a level of abstract acceptance to certain non-native species. It comes as a complete surprise to most people that the Ring Necked Parakeet is now accepted as a naturalised species of the British Isles. Ironically leopards which were present in Britain till at least 12 thousand years ago would not be considered to be a native animal even if one was caught in the wild. There are many rumours attributed to how the parakeet population started, even so it is probable only a hand few of escaped birds were accountable for today’s population of 4000.

It is largely accepted that viable populations of larger potentially dangerous animals could not form from a few escapees, however contrary to this belief this has happened in the case of wild boar, coypu and wallabies on our small crowded Island and in recent times. Even if large cats like leopards or pumas were turned loose what is the probability there were sufficient numbers released at the same time without a national emergency?

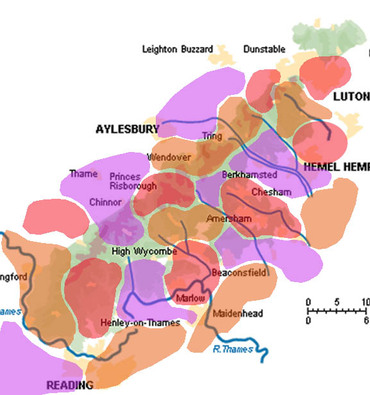

This Blog is a diary of my ongoing research to explore and draw some conclusions on the viabilitiy of a current population. I am to create a series of maps which will utilise sightings data, land use types, habitats and landscape corridors to illustrate the possabilities and facts.

Paulo Nicolaides.

As discussed in my previous articles I don’t believe the issue lies with Britain’s human population, available wilderness or spatial arrangement. In order to investigate the possibility a big cat population we

need to consider and compare an array of scenarios and examples of other species introduction, re-establishment or naturalisation elsewhere in the world.

Humans have a great ability to misinterpret the context in which living organisms interact with our modern landscape. In the majority of British gardens less than 15% of plants are native to our own shores, even our lawns are foreign most of which contain domesticated grass strains from the Americas. Naturalisation as the word indicates can be a natural process of succession where all species within an ecosystem jostle for position some will become extinct, some will thrive, and others will change to fill new niches.

In Britain our separation from mainland Europe has strengthened the boundary’s to what is native and what isn’t, except from the last ice age anyway. A list of species naturalised to Britain can be seen in schedule 9 of the Wildlife & Countryside Act 1981 giving a level of abstract acceptance to certain non-native species. It comes as a complete surprise to most people that the Ring Necked Parakeet is now accepted as a naturalised species of the British Isles. Ironically leopards which were present in Britain till at least 12 thousand years ago would not be considered to be a native animal even if one was caught in the wild. There are many rumours attributed to how the parakeet population started, even so it is probable only a hand few of escaped birds were accountable for today’s population of 4000.

It is largely accepted that viable populations of larger potentially dangerous animals could not form from a few escapees, however contrary to this belief this has happened in the case of wild boar, coypu and wallabies on our small crowded Island and in recent times. Even if large cats like leopards or pumas were turned loose what is the probability there were sufficient numbers released at the same time without a national emergency?

This Blog is a diary of my ongoing research to explore and draw some conclusions on the viabilitiy of a current population. I am to create a series of maps which will utilise sightings data, land use types, habitats and landscape corridors to illustrate the possabilities and facts.

Paulo Nicolaides.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed